Humanity will be divided as never before by climate change, with the world's poor its disproportionate victims, the latest United Nations report on the coming effects of global warming made clear yesterday.

Existing divisions between rich and poor countries will be sharply exacerbated by the pattern of climate-change impacts in the coming years, predicted in the study from the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Increased drought, crop failure, disease, extreme weather events and sea level rise are all likely to fall much more heavily on struggling populations in Africa, Asia and South America than on the rich industrial societies of Europe, North America and Australia - who have done most to cause global warming through greenhouse gas emissions in the past, and who are best able to afford counter-measures to limit its consequences.

This picture of great inequity and a great climate divide was seized on by aid agencies and environmental pressure groups. "Governments must act now to stop a catastrophe for the world's poor," said Benedict Southworth, director of the anti-poverty charity the World Development Movement. "Climate change is no longer just an environmental issue, it is a looming humanitarian catastrophe," said Friends of the Earth International's climate campaigner, Catherine Pearce.

The IPCC chairman, Rajendra Pachauri, said in launching the report: "The poorest of the poor in the world - and this includes poor people in prosperous societies - are going to be the worst hit. People who are poor are least able to adapt to climate change."

The study, endorsed by all the major UN member states, was the second part of the IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report, or AR4. The first part, released in Paris two months ago, dealt with the science of climate change and likely future temperature rises. Yesterday's report goes on to detail the potential impacts of those rises on the natural world and on human society.

It was released in Brussels only after an all-night argument in which some countries responsible for increasingly high greenhouse gas emissions, led by China, the US and Saudi Arabia, succeeded in watering down the text from its initial draft.

However, the picture painted by the final consensus document was stark enough, setting out the dire consequences of global warming, sector by sector and region by region, if strong action is not taken to limit its effects.

The impacts are already visible, the report said, with significant changes due to rising temperatures now apparent in ice masses, water bodies, agriculture and ecosystems. Changes consistent with higher temperatures have been noted in 29,000 sets of data and 75 separate studies; they range from melting permafrost in Arctic regions to shifting distributions of fish populations, and earlier timing of spring events such as leaf-unfolding, bird-migration and egg-laying.

But it is the future impacts that are potentially catastrophic. The report sets out changes likely in the years to come in freshwater resources, food, coastal systems, communities, health and natural ecosystems.

In the last-named, they are quite extraordinary. Up to 30 per cent of plant and animal species so far assessed are likely to be at increased risk of extinction if increases in global temperature exceed 1.5-2.5C, the report says.

A picture of a great climate-change divide between rich and poor countries becomes startlingly visible in the report. Africa is the worst case. Some of the projected changes are horrifying - and only just around the corner. "By 2020, between 75 and 250 million people [in Africa] are projected to be exposed to an increase of water stress due to climate change," the report says.

African agricultural production is projected to be "severely compromised by climate variability and change," with decreases likely in the area suitable for agriculture, the length of the growing season and yield potential. "In some countries, yields from rain-fed agriculture could be reduced by up to 20 per cent by 2020," the report says.

Asia is not far behind, with many negative impacts expected. They include a water "double whammy" as Himalayan glaciers irreversibly melt - first, increased flooding in glacier-fed rivers from the meltwater, then decreased water resources as the glaciers disappear.

Asian coastal areas, especially the big cities in the seven "mega-deltas" from India's Ganges to China's Yangtze, will be at greatly increased risk of flooding, with an associated increase in death to due to diarrhoeal disease, while by 2050, crop yields in central and south Asia may drop by 30 per cent.

In Latin America, water supplies available for human consumption, agriculture and energy generation are predicted to be "significantly affected" by changes in rainfall patterns and the disappearance of Andean glaciers. Parts of the Amazon rainforest are likely to turn into semi-arid savannah.

In the richer continents the effects, at least in the short term, will not be as severe, and will be easier to defend against. Indeed, some may be beneficial for a time: in the warming atmosphere, crop yields in North America may rise by up to 20 per cent, and there may be some agricultural benefits for Australasia. Europe will have to deal with the likely disappearance of skiing, more heatwaves and an increase in flash flooding - but not starvation.

However, in the long term, the report says, any temporary benefits will be overwhelmed by the damage rising temperatures will wreak all over the globe.

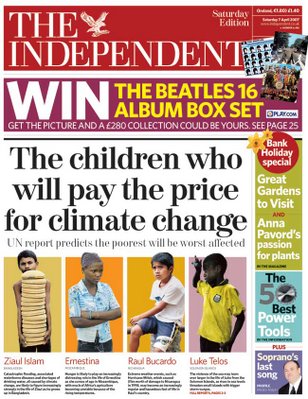

The children who will pay the price for climate change

Ziaul Islam, BANGLADESH

Catastrophic flooding, associated waterborne diseases and shortages of drinking water, all caused by climate change, are likely to figure increasingly strongly in the life of Ziaul as he grows up in Bangladesh.

Ernestina, MOZAMBIQUE

Hunger is likely to play an increasingly distressing role in the life of Ernestina as she comes of age in Mozambique, with much of Africa's agriculture becoming unviable because of the rising temperatures.

Raul Bucardo, NICARAGUA

Extreme weather events, such as Hurricane Mitch which devastated his country's capital Tegucigalpa in 1998, may become an increasingly regular and hazardous fact of life in Nicaragua where Raul lives.

Luke Telos, SOLOMON ISLANDS

The violence of the sea may loom ever larger in the life of Luke from the Solomon Islands, as rises in sea levels threaten small islands with bigger storm-surges.

Source: The Independent

No comments:

Post a Comment