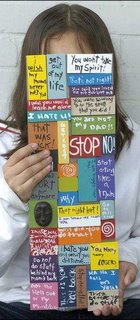

A collaborative piece called ``Finding Our Voice’’ is composed of moveable magnets with phrases written by the children. It’s what they wish they could have said to their abusers.JEFFREY S. OTTO / NYTRNG

A collaborative piece called ``Finding Our Voice’’ is composed of moveable magnets with phrases written by the children. It’s what they wish they could have said to their abusers.JEFFREY S. OTTO / NYTRNGART THERAPY TREATMENTS

Children’s art can reflect symptoms of sexual abuse.

For example:

Children with a fragmented sense of self might paint non-anatomical portraits scattering their body parts on the page.

Those with inappropriate interest or knowledge of sexual acts might decorate arm and hand casts with manicured nails, representing the sexualized behavior of young girls.

Counselors also match art projects with abuse symptoms:

Symptom: Depression

Treatment: Drawing is not used because it keeps a child in the two-dimensional realm, so sculpture is encouraged

Symptom: Low self-esteem

Treatment: Sculpting with clay to give the child control

Symptom: Refusing to speak

Treatment: Painting, playing with puppets and creating stories using figurines to allow child to communicate easier

Learn more

According to the American Art Therapy Association, art therapy first became a profession in the 1940s, about the same time psychiatrists began studying the art of mentally ill patients and educators realized children’s art expressed developmental, emotional and cognitive growth.

In 2000, the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services’ National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect counted 879,000 substantiated cases of child maltreatment, 10 percent of which were sexual abuse

Art helps heal wounds of children who’ve been sexually abused

Paint the monsters in your head, the children were told.So, armed with newsprint, construction paper and tempura paints, they created ``Mr. Peach-head’’ and ``The Evil-Thrown-In-Your-Face’’ creatures.

If you didn’t know these children’s stories, you’d think the monsters represented people who had harmed them.

But to this group of sexually abused children, the monsters are self-portraits.

``Not all kids feel good inside,’’ said Tai Kulenic, an art therapist at the Carousel Center in Wilmington, N.C., where children who have been abused go for treatment. ``They feel the yuck; feel like others can see the yuck on them.

’’That was the way 11-year-old Marie, not her real name, felt about herself after her mother’s boyfriend beat and sexually molested her for a year when she was 8.

``He would come home drunk sometimes and beat us for nothing or get angry and beat me and my sister,’’ Marie said, telling her account in a calm, detached tone.

She mustered courage to remove herself and her little sister from her mother’s care for the safe haven of her father. Soon after, art became her salvation.

``Art is like a best friend for me. You can trust it,’’ she said. ``You can do anything with it, and it turns out nice.’’

Personal trauma like sexual abuse affects the family, community and often shows up in the classroom, Kulenic said. Using art as therapy can help by bringing something positive to the situation.

FINDING THEIR VOICES

This art is not about beauty or being happy. Smiles in the self-portraits don’t mean the artists were glad. There’s pain behind each mask.

But with each completed clay sculpture or painting, there is hope, too. Hope for recovery. Hope their abusers won’t return.

A collaborative piece called ``Finding Our Voice,’’ composed of moveable magnets with phrases written on them, stemmed from an exercise in which the children were asked what they wished they could have said to their abusers — if they knew they wouldn’t get hurt or in trouble.

A staccato of hatred, determination and anger appears on the magnets:

- ``You won’t take my spirit.’’

- `I hate you. I wish I didn’t know you. I wish you were dead.’’

- ``This is your payback.’’

In a trust-building session, the children allowed Kulenic to make plaster casts of their hands and arms. Then, they decorated the molds.

``When you see their hands, it personalizes their experience without violating their privacy, helping to protect these kids,’’ said Kevin Lee, executive director of the center.

In another activity, the children were asked to paint found tree branches to create ``power sticks.’’

``In trauma and abuse, power has to be re-visioned for them,’’ Kulenic said. ``It’s not power over someone but realizing the power in yourself.’’

Many times, Kulenic said the first hurdle for therapists and doctors is gaining the child’s trust.

Some want to talk, others are selectively mute. But art can break the barriers children build for themselves so investigators and doctors can learn what happened.

``Art therapy provides access to nonverbal memories of a trauma through a nonverbal medium,’’ she said, so children can paint what happened to them, even when their vocabulary isn’t advanced enough to relate it.

``Children face their trauma, tell their story and put it into a new context that, over time, makes the memory manageable.’’

HEALING BEGINS

Gradually, art can lead to conversations with therapists about their abuse.

``Mr. Peach-head’’ came from a session with a 7-year-old girl who wouldn’t speak to doctors.

Kulenic left her door open in the next room, spread out some newspaper on the floor and started painting. Soon, the little girl became curious, wandered into her room and started painting beside Kulenic.

``She didn’t talk to me until two or three sessions later,’’ she said. ``I just let her paint her monster, and it all gradually came out through a year and a half of therapy.’’

Sometimes Kulenic asks questions while they paint, mold clay or play in a sand tray. Sometimes she just listens.

With Marie, Kulenic is helping her get angry — in a healthy way.

``Some kids want to protect and think, `If I don’t tell, then he’ll just abuse me and not the other kids,’ ’’ Kulenic said, ``so sometimes I have to get kids like Marie to get in touch with their anger to express it and talk about it.’’

Working through her problems with art has given Marie the strength to help other abused children.

``My friend last year had told me that she had been sexually abused, too, and I told her she needed to go to the school counselor and that I couldn’t keep that secret,’’ Marie said. ``She asked if I would go with her, and I did.’’

The man was arrested but soon was released and returned to live with her friend’s family.

Marie’s story has a happier ending.

After her recent testimony in the trial of her mother’s boyfriend, he was sentenced to nine years in prison.

Marie was in the fifth-grade when she first reported her abuse. Her high marks in math and spelling slipped to Fs. Today, her grades are returning to normal.

``I forgot about some of it, and I’m trying to forget the rest,’’ she said.

``I’m not that scared now to talk because if I was living with my mom, no one would hear me. But now that I’m living with my dad and my step-mom, they help me.’’

(Amanda Greene writes for the Star-News in Wilmington, N.C.)

By Amanda GreeneNYT Regional Newspapers

No comments:

Post a Comment